On the first morning in Delhi, the jet lag sat heavy in the lobby of Shangri-La. Stanford MBAs were trying their best to be awake, sipping tea beneath chandeliers, eyes still foggy from the 16-hour flight. There were seventeen first-years (or “MBA1s”), four second-years (MBA2s), plus their professor, Yossi Feinberg , and staff advisor Ming Chu. All came to India for the Global Study Trip, a Stanford Business School tradition in which students visit countries and immerse themselves in its business fabric.

The objective this time was growth and innovation in India, something that sounded clean on paper, the sort of thing you’d write on a syllabus. In reality, though, India is a place that resists syllabi. The country offers you contradictions in every direction: QR codes on street-side coconut stalls, ministers talking about Mars missions, Bollywood stars who double as entrepreneurs, investors who cite the Ramayana to define leadership. For the students, the week would be less about learning what India “is” and more about getting comfortable with the fact that it can be many things at once.

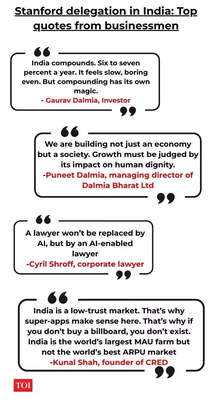

The first to meet them was Gaurav Dalmia, investor, essayist, philosopher. He greeted the group in his home and reached backward in time. India, he said, had been prosperous for most of history, before the West discovered more efficient ways to organize capital and trade. Its resurgence now would not look like China’s rocket-fuel sprint. “India compounds,” he told them. “Six to seven percent a year. It feels slow, boring even. But compounding has its own magic.”

The students were inspired, though still recovering from the jet lag. They had read about India’s GDP figures before, but Dalmia’s framing was different. Not hockey sticks but patience. And then he opened a copy of the Ramayana and read aloud the qualities of an ideal leader: grateful, truthful, versatile, patient, slow to anger, free of envy, yet terrifying when provoked. A few students looked up, surprised. Was this an epic poem or a CEO job description? Dalmia smiled. “Indian philosophy is not abstract,” he said. “It is applied leadership.”

The group left buzzing, trying to reconcile what they’d heard with the India outside the windows, with horns blaring, construction cranes looming, roadside tea vendors serving to crowds that never seemed to thin.

The evening brought Puneet Dalmia of Dalmia Bharat, whose cement plants have built many of the highways the students drove on. He spoke of India’s four “I’s”: Intent, Ideas, Independence, Individuals. Intent is what the state must set; ideas are the spark of entrepreneurs; independence is the freedom to act without capture; and individuals (the people) are the multiplier.

But he also quoted from ancient texts and Harvard research, toggling between scriptures and slides. Happiness, he said, cannot be measured only in stock prices or steel output. “We are building not just an economy,” he said, “but a society. Growth must be judged by its impact on human dignity.”

It was early in the trip, but already the students noticed a pattern: Indian business leaders often spoke in two registers, one of GDP, capital markets, and tech; another of values, philosophy, and family. In Silicon Valley, that combination might sound like posturing. Here, it felt woven into the operating system.

The evening was unlike anything the students had experienced. Thanks to Dalmia, Indian Accent, normally tucked away in a sleek Delhi hotel, had been transported inside the Red Fort. Servers carried out daulat ki chaat under Mughal arches, blue cheese naan in the shadow of ramparts where emperors once surveyed their kingdom. It was haute cuisine against a backdrop of empire. When the plates were cleared, the courtyard darkened, and the sandstone walls came alive with the sound-and-light show: Shah Jahan commissioning the fort, the British seizing it, Nehru’s voice declaring independence in 1947.

The next day, Sanjeev Bikhchandani sat down with the delegation and told his story about building Naukri. During MBA placement season, Bikhchandani noticed: “Talent is scarce, and markets don’t lie.” He began photographing public placement records and selling the data as a survey. That instinct (observe behavior, package insight) became Naukri.com, India’s first big internet success.

His lessons amazed the delegation with unusual force: ‘Clunky but dense’ beats ‘slick but sparse’. Customer insight beats capital. In downturns, when others cut, spend more. “Be frugal in bubbles, bold in busts,” he told them.

Agra was the trip’s postcard moment. The buses pulled up at 10AM, and suddenly the Taj Mahal was no longer a photograph in a textbook but a living presence. Students wandered its marble terraces in awe, tracing inlay work with their fingers, staring at the perfect symmetry that somehow still felt human. Some tried to capture it on their phones, only to realize no lens could hold the shimmer of white stone against a pale morning sky.

Later, the group regrouped for lunch at the Oberoi Amarvilas, where every dining-room window frames the monument like a painting. Between courses, heads kept drifting toward the view, as if the Taj were a third guest at the table. By afternoon, India reminded them of its unpredictability: a sudden downpour sent the delegation running into a makeshift roadside restaurant, plastic chairs and steaming chai serving as impromptu refuge. When the rain eased, they climbed back into their buses, damp but elated. It was the kind of day that felt both choreographed and accidental: iconic grandeur, sudden chaos, and the luck of experiencing both in a single sweep.

In Mumbai, they met Manish Kejriwal, private equity veteran at Kedaara. Unlike the spreadsheets they were used to at Stanford, Kejriwal described investing as anthropology. Triangulate character, not just numbers. Build dissent into your firm so the junior analyst feels safe disagreeing with the partner. “We have an obligation to dissent,” he said.

He spoke of India not as one market but as a mosaic of states, families, informal networks. His preference was for shovels over gold mines: workflow software and data services.

At The Times of India offices, Sivakumar Sundaram and his colleagues put together an insightful session using interactive polls and a live thinking session. “There isn’t one India,” Sundaram said. “There are three.”

Later, Cyril Shroff, India’s most famous corporate lawyer, met the students in his Peninsula Towers office. His firm, once boutique, now has sixty percent women. He spoke of India’s legal system as both bottleneck and backbone: slow courts, yes, but a structure that undergirds growth.

More striking was his framing of India’s independence. The country, he said, had moved from importing regulation to exporting it: Aadhaar as a model for digital identity, UPI for payments. “A lawyer won’t be replaced by AI, but by an AI-enabled lawyer.” In Silicon Valley, AI was usually pitched as disruption. Here, it was augmentation.

Kunal Shah’s talk moved the group. The founder of CRED spoke less like a startup CEO and more like a philosopher. “India is a low-trust market,” he said. “That’s why super-apps make sense here. That’s why if you don’t buy a billboard, you don’t exist.”

He shared some specific, unique facts: 37 GB of mobile data per Indian per month, but only 20M consumers drive 80% of online GMV. YouTube earns just $3 per Indian user annually. “India is the world’s largest MAU farm,” he said, “but not the world’s best ARPU market.”

He spoke of status as the true currency: uniforms over paychecks, weddings as theater, caste layered into speech. “You can underpay people if you give them status,” he joked. He warned that subsidies dull ambition, that ambition comes from hunger, and that AI risks making people mentally lazy. “The tool that makes you atrophy is also the gym,” he said, cryptically. Many loved his candor but no one forgot it.

An interesting setting came with Piyush Goyal, India’s Minister of Commerce. In a wood-paneled room, he began by congratulating Stanford, after which he pivoted to geopolitics.

India, he said, has a habit of turning crises into opportunities. Buying discounted Russian oil when the West sanctioned it. Launching a Mars mission for $50M. Remaining “multi-aligned” instead of non-aligned: friends with Washington, Moscow, and Tel Aviv all at once.

On AI, he said that “the human mind will remain supreme.” On trade, he was clear that every country makes its choices. On culture, he urged students to witness Ganesh Chaturthi in Mumbai. “Religion here binds people, creates mass fervor, unites the country,” he said.

Not all sessions were with businessfolk and ministers. At a nonprofit panel hosted by Melody Mortazavi and Sanjiv Kaura, the students heard from Melody, Sanjiv, the alumni of Teach India, and more changemakers. One of the alumni had gone from Domino’s store manager to retail executive. Another described education as emancipation.

For many in the delegation, these stories carried as much weight as the macroeconomics. They put faces to the abstractions of “India 2” and “India 3.”

Through it all, Yossi played the role of quiet provocateur. On buses and over breakfasts, he asked questions that unsettled neat conclusions. If India has the cheapest data in the world, why does it have one of the lowest female labor participation rates? If it can build UPI for street vendors, why are courts so slow? If it can send a probe to Mars, why do so few Indians have access to credit?

By the end, the trip felt less like a syllabus and more like a kaleidoscope. From Dalmia’s compounding to Bikhchandani’s salary surveys, from Shroff’s AI lawyers to Shah’s philosophy of status, from Goyal’s geopolitics to Teach India’s alumni, the delegation had been shown many Indias .

On the final evening, standing on the balcony in Malabar Hill, the students looked out over the city as drums from Ganesh processions echoed through the streets. Someone remarked, “We came looking for lessons in growth. What we found were lessons in resilience, trust, and contradictions.”

The reflections were about how the trip itself felt. “We’ve been treated like family everywhere we’ve gone,” said David Pantera, marveling at the warmth of the hospitality. Katy Dolan wrote to the student leaders that the week had “vastly exceeded expectations,” plus a reminder that a trip that had looked seamless to participants had in fact been an intense labor of love from the four MBA2s who led with grace and humor. And for Cayla Davis, the experience “exceeded her wildest imagination,” not just for the meetings and sights but for the thoughtfulness and care woven into the group dynamic.

India, folks realized, is not a case study. It is a billion-person startup, a civilization in beta, a place where compounding is destiny and paradox the default mode.

And for Stanford’s delegation, that was the real education.

The objective this time was growth and innovation in India, something that sounded clean on paper, the sort of thing you’d write on a syllabus. In reality, though, India is a place that resists syllabi. The country offers you contradictions in every direction: QR codes on street-side coconut stalls, ministers talking about Mars missions, Bollywood stars who double as entrepreneurs, investors who cite the Ramayana to define leadership. For the students, the week would be less about learning what India “is” and more about getting comfortable with the fact that it can be many things at once.

The first to meet them was Gaurav Dalmia, investor, essayist, philosopher. He greeted the group in his home and reached backward in time. India, he said, had been prosperous for most of history, before the West discovered more efficient ways to organize capital and trade. Its resurgence now would not look like China’s rocket-fuel sprint. “India compounds,” he told them. “Six to seven percent a year. It feels slow, boring even. But compounding has its own magic.”

The students were inspired, though still recovering from the jet lag. They had read about India’s GDP figures before, but Dalmia’s framing was different. Not hockey sticks but patience. And then he opened a copy of the Ramayana and read aloud the qualities of an ideal leader: grateful, truthful, versatile, patient, slow to anger, free of envy, yet terrifying when provoked. A few students looked up, surprised. Was this an epic poem or a CEO job description? Dalmia smiled. “Indian philosophy is not abstract,” he said. “It is applied leadership.”

The group left buzzing, trying to reconcile what they’d heard with the India outside the windows, with horns blaring, construction cranes looming, roadside tea vendors serving to crowds that never seemed to thin.

The evening brought Puneet Dalmia of Dalmia Bharat, whose cement plants have built many of the highways the students drove on. He spoke of India’s four “I’s”: Intent, Ideas, Independence, Individuals. Intent is what the state must set; ideas are the spark of entrepreneurs; independence is the freedom to act without capture; and individuals (the people) are the multiplier.

But he also quoted from ancient texts and Harvard research, toggling between scriptures and slides. Happiness, he said, cannot be measured only in stock prices or steel output. “We are building not just an economy,” he said, “but a society. Growth must be judged by its impact on human dignity.”

It was early in the trip, but already the students noticed a pattern: Indian business leaders often spoke in two registers, one of GDP, capital markets, and tech; another of values, philosophy, and family. In Silicon Valley, that combination might sound like posturing. Here, it felt woven into the operating system.

The evening was unlike anything the students had experienced. Thanks to Dalmia, Indian Accent, normally tucked away in a sleek Delhi hotel, had been transported inside the Red Fort. Servers carried out daulat ki chaat under Mughal arches, blue cheese naan in the shadow of ramparts where emperors once surveyed their kingdom. It was haute cuisine against a backdrop of empire. When the plates were cleared, the courtyard darkened, and the sandstone walls came alive with the sound-and-light show: Shah Jahan commissioning the fort, the British seizing it, Nehru’s voice declaring independence in 1947.

The next day, Sanjeev Bikhchandani sat down with the delegation and told his story about building Naukri. During MBA placement season, Bikhchandani noticed: “Talent is scarce, and markets don’t lie.” He began photographing public placement records and selling the data as a survey. That instinct (observe behavior, package insight) became Naukri.com, India’s first big internet success.

His lessons amazed the delegation with unusual force: ‘Clunky but dense’ beats ‘slick but sparse’. Customer insight beats capital. In downturns, when others cut, spend more. “Be frugal in bubbles, bold in busts,” he told them.

Agra was the trip’s postcard moment. The buses pulled up at 10AM, and suddenly the Taj Mahal was no longer a photograph in a textbook but a living presence. Students wandered its marble terraces in awe, tracing inlay work with their fingers, staring at the perfect symmetry that somehow still felt human. Some tried to capture it on their phones, only to realize no lens could hold the shimmer of white stone against a pale morning sky.

Later, the group regrouped for lunch at the Oberoi Amarvilas, where every dining-room window frames the monument like a painting. Between courses, heads kept drifting toward the view, as if the Taj were a third guest at the table. By afternoon, India reminded them of its unpredictability: a sudden downpour sent the delegation running into a makeshift roadside restaurant, plastic chairs and steaming chai serving as impromptu refuge. When the rain eased, they climbed back into their buses, damp but elated. It was the kind of day that felt both choreographed and accidental: iconic grandeur, sudden chaos, and the luck of experiencing both in a single sweep.

In Mumbai, they met Manish Kejriwal, private equity veteran at Kedaara. Unlike the spreadsheets they were used to at Stanford, Kejriwal described investing as anthropology. Triangulate character, not just numbers. Build dissent into your firm so the junior analyst feels safe disagreeing with the partner. “We have an obligation to dissent,” he said.

He spoke of India not as one market but as a mosaic of states, families, informal networks. His preference was for shovels over gold mines: workflow software and data services.

At The Times of India offices, Sivakumar Sundaram and his colleagues put together an insightful session using interactive polls and a live thinking session. “There isn’t one India,” Sundaram said. “There are three.”

- India 1: the top 100 million, global in outlook, on Netflix and credit cards.

- India 2: the aspiring middle, mobile-first, leapfrogging basic infrastructure.

- India 3: rural, cash-driven, still outside the formal economy.

Later, Cyril Shroff, India’s most famous corporate lawyer, met the students in his Peninsula Towers office. His firm, once boutique, now has sixty percent women. He spoke of India’s legal system as both bottleneck and backbone: slow courts, yes, but a structure that undergirds growth.

More striking was his framing of India’s independence. The country, he said, had moved from importing regulation to exporting it: Aadhaar as a model for digital identity, UPI for payments. “A lawyer won’t be replaced by AI, but by an AI-enabled lawyer.” In Silicon Valley, AI was usually pitched as disruption. Here, it was augmentation.

Kunal Shah’s talk moved the group. The founder of CRED spoke less like a startup CEO and more like a philosopher. “India is a low-trust market,” he said. “That’s why super-apps make sense here. That’s why if you don’t buy a billboard, you don’t exist.”

He shared some specific, unique facts: 37 GB of mobile data per Indian per month, but only 20M consumers drive 80% of online GMV. YouTube earns just $3 per Indian user annually. “India is the world’s largest MAU farm,” he said, “but not the world’s best ARPU market.”

He spoke of status as the true currency: uniforms over paychecks, weddings as theater, caste layered into speech. “You can underpay people if you give them status,” he joked. He warned that subsidies dull ambition, that ambition comes from hunger, and that AI risks making people mentally lazy. “The tool that makes you atrophy is also the gym,” he said, cryptically. Many loved his candor but no one forgot it.

An interesting setting came with Piyush Goyal, India’s Minister of Commerce. In a wood-paneled room, he began by congratulating Stanford, after which he pivoted to geopolitics.

India, he said, has a habit of turning crises into opportunities. Buying discounted Russian oil when the West sanctioned it. Launching a Mars mission for $50M. Remaining “multi-aligned” instead of non-aligned: friends with Washington, Moscow, and Tel Aviv all at once.

On AI, he said that “the human mind will remain supreme.” On trade, he was clear that every country makes its choices. On culture, he urged students to witness Ganesh Chaturthi in Mumbai. “Religion here binds people, creates mass fervor, unites the country,” he said.

Not all sessions were with businessfolk and ministers. At a nonprofit panel hosted by Melody Mortazavi and Sanjiv Kaura, the students heard from Melody, Sanjiv, the alumni of Teach India, and more changemakers. One of the alumni had gone from Domino’s store manager to retail executive. Another described education as emancipation.

For many in the delegation, these stories carried as much weight as the macroeconomics. They put faces to the abstractions of “India 2” and “India 3.”

Through it all, Yossi played the role of quiet provocateur. On buses and over breakfasts, he asked questions that unsettled neat conclusions. If India has the cheapest data in the world, why does it have one of the lowest female labor participation rates? If it can build UPI for street vendors, why are courts so slow? If it can send a probe to Mars, why do so few Indians have access to credit?

By the end, the trip felt less like a syllabus and more like a kaleidoscope. From Dalmia’s compounding to Bikhchandani’s salary surveys, from Shroff’s AI lawyers to Shah’s philosophy of status, from Goyal’s geopolitics to Teach India’s alumni, the delegation had been shown many Indias .

On the final evening, standing on the balcony in Malabar Hill, the students looked out over the city as drums from Ganesh processions echoed through the streets. Someone remarked, “We came looking for lessons in growth. What we found were lessons in resilience, trust, and contradictions.”

The reflections were about how the trip itself felt. “We’ve been treated like family everywhere we’ve gone,” said David Pantera, marveling at the warmth of the hospitality. Katy Dolan wrote to the student leaders that the week had “vastly exceeded expectations,” plus a reminder that a trip that had looked seamless to participants had in fact been an intense labor of love from the four MBA2s who led with grace and humor. And for Cayla Davis, the experience “exceeded her wildest imagination,” not just for the meetings and sights but for the thoughtfulness and care woven into the group dynamic.

India, folks realized, is not a case study. It is a billion-person startup, a civilization in beta, a place where compounding is destiny and paradox the default mode.

And for Stanford’s delegation, that was the real education.

You may also like

Sam Thompson enjoys 'cosy chat' with Love Island star ex Samie Elishi at NTAs

'I visited picturesque UK 'seaside town' but one thing makes it unique'

Tvesa Malik aims for redemption at Swiss Ladies Open

NIA recovers three grenades, pistol in Amritsar temple grenade attack case

Win a Stay in an English Heritage Holiday Cottage